How I learned to get a grip by embracing "opposable opinions"

The software engineer bristles with annoyance, then cringes in fear. The cause? They came face to face with an opposable opinion. What are these opposable opinions and is it possible to refactor our brain to respond better the next time we’re confronted with one of them? Read on, fair coder!

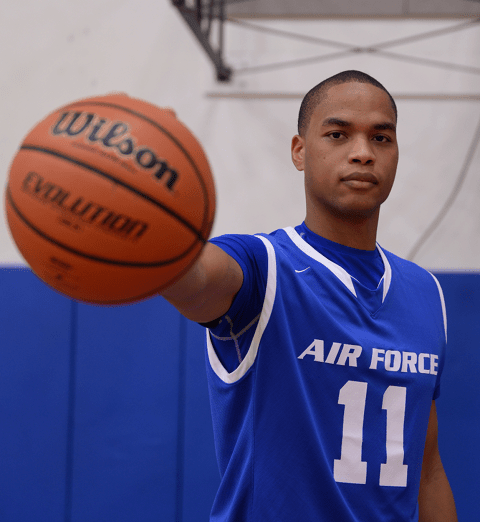

Let’s start with this illustration: Have you ever seen a basketball player “palm” a basketball? It’s a coveted feat which greatly enhances a player’s control of the ball. Even players with relatively small hands can do it, provided they have sufficient grip strength. But try to palm a basketball without using your thumb. Suddenly it’s a lot more difficult, and ball control is dramatically reduced.

Each of your two hands is equipped with an opposable thumb, enabling you to perform intricate tasks as mundane as tying your shoelaces and as precise as soldering components on a circuit board. Though you probably take them for granted, you appreciate your opposable thumbs. But here’s a question: are you open to opposable opinions? Let’s explore the utility of the opposable thumb as an illustration for the need to seek out additional opinions, especially dissenting opinions. You’ll see how embracing these opposable opinions will improve your “grip” on software projects large and small.

But first, what exactly does it mean that your thumb is “opposable?”

Digital dexterity and the opposable thumb

Check out this definition of “opposable” from dictionary.com :

opposable ([uh-poh-zuh-buh l])

adjective

1. capable of being placed opposite to something else:

the opposable thumb of primates.

2. capable of being resisted, fought, or opposed.

The ability of the thumb to “oppose” the fingers is super important. Consider a few tongue-in-cheek examples.

- At your next whiteboard interview, hold the dry-erase marker without using your thumb.

- Tabs vs. spaces? In any case, try entering spaces without using your thumbs.

- Give your surly cube neighbor a thumbs up without showing your thumb. Hope they mistake the gesture for an awkward attempt at a fist bump instead of an aggressive challenge.

- O_o

Why embrace opposable opinions?

With the opposable thumb in mind, what does it mean to have an “opposable opinion?” Read definition 2 of “opposable” again: “capable of being resisted, fought, or opposed.”

Does anyone ever try to “oppose” your ideas? If so, do you puff up like a turkey and run them off? Are you open to any “pushback” during design, code review, etc.? Remember, willingness to feel out opposing opinions won’t make you weaker. Just like thumb and forefinger work together to perform tasks that neither could accomplish alone, your openness to different points of view will only make your work better.

Imagine a young index finger named Mr. Pointe. Mr Pointe lives in its own little thumbless world. He doesn’t realize what he can’t accomplish. To listen to him ramble on in his thick accent, he’s doing just fine: “I finger paint works of art that Mom puts on the fridge! I point at stuff, especially everyone else’s flaws. With a crook of my joints I beckon those in need of punishment. I unlock my owner’s phone! Search and rescue in the nasal cavities? Done, done, and done. I relieve itches, type 7 WPM. There’s nothing I can’t do!” Yes, Mr. Pointe thinks he’s pretty great.

It’s plain for the outsider to see that Mr. Pointe could really use the assistance of Mrs. Thumb if he wants to accomplish any real work. For that matter Mrs. Thumb isn’t so great on her own either. Both need to work together — in opposition to one another — in order to get a handle on greatness.

Consideration of opposable opinions makes for better problem solving

When searching for the optimal solution to a problem, we should try to generate as many ideas and approaches to the problem as possible. This is known as divergence. For an example, see the Double Diamond process used by many designers to generate the ideal strategy and execution plan in a given problem space. If you’re too quick to dismiss opposing ideas, the converged-upon solution will likely be suboptimal. Indeed, if you never have more than one idea, you’re not really “converging” on a solution. You’ll arrive at the answer quickly, but will it be correct?

Opposable opinion avoidance — Running from the thumbs

With tens of thousands of different intelligent minds in our field, we ought to be able to harness the power between our “opposing opinions” and forge better software solutions for our users. Unfortunately, in many venues people avoid any exposure to ideas opposing their own. Consider examples in social media and the workplace.

Avoidance in social media

On social media, people follow others who think the same way as them. It’s like they’re divided into camps composed of endless rows of index fingers. What happens? They unwittingly engage in groupthink. The quality of their ideas suffers. Unfounded and illogical arguments are strengthened by a massive feedback loop inside an echo chamber. Compassion and empathy plummet. Outsiders are ridiculed. Hateful and exclusive speech blossoms. No thumbs allowed.

Avoidance in the workplace

Traditional command-and-control style management often discourages differences of opinion. Any contradiction, actual or perceived, may be viewed as insubordinate and punished accordingly. By their words and actions, these dictator types intimate, “All my ideas are amazing. All ye naysaying peons need but carry out my vision and bask in my digital glory.” For the most part the dictator types fall flat on their face eventually, often leaving a trail of destruction in their wake.

Why we avoid opposable opinions — The story of the insecure index finger

Imagine an index finger standing tall and confident. It is going to attempt to lift a basketball when suddenly it catches sight of a bulbous monstrosity coming its way. It’s a thumb! O_o. Noooo.

Immediately the finger breaks into a cold sweat. A challenger! The finger steels itself for the attack, ensuring its fingernail is sharp and its fellow fingers are aligned in battle formation. “All hands, brace for impact!” The thumb is confused, “Dude. I just wanted to help you lift that basketball.”

Honestly, do feel like that finger sometimes when someone pops an opposing opinion, challenging one of your ideas? “Brace for impact! Run away!” Why do we avoid “thumbs”? Consider a few possibilities.

Lack of confidence: “That thumb will crush me!”

Weak stance

Lack of confidence manifests itself in so many ways. Perhaps deep down we feel that our stance on an issue is shaky and we don’t really know how to defend it. For example, an individual raised by the founding members of the Flat Earth Society might feel strongly about their belief in a flat earth and feel a connection to the community. Yet they will likely lack confidence in their ability to transmit and defend their belief to unbelievers. If you lack confidence in your stance on an issue, the key is education. Educate yourself about the issue and the various arguments involved, for or against. Say you feel strongly that your team should write everything in Go for its next project. Why? Educate yourself regarding the pros and cons. Defend your position with confidence.

Technical abilities: “Have you tried turning it off and on again?”

We might also lack confidence in our technical abilities. This could be manifest as a case of imposter syndrome, where we feel our technical skills are unworthy of the accolades and monetary compensation we’ve received. If someone you view as technically superior challenges your idea or position, you might be tempted to just run and hide. To bolster confidence in your technical abilities, you need two things: 1) Keep learning and honing your craft. Don’t stop reading. Never stop practicing. 2) Measure your expectations. It’s impossible to know everything in this field. Use what you know and move forward. Don’t pretend to know everything, and don’t be afraid to admit to not knowing. Ask questions.

Communication skills: “I, Um… You know.”

Sometimes we lack confidence in our **ability to communicate **our ideas. We might feel very confident in our technical skills and be 99% sure that our stance is the correct one. Yet our problem is one of communication: How do I effectively transmit this knowledge to others? We give up trying, and run away from people and situations that force us to communicate. I would argue that communication is actually the hardest part of programming — maybe the hardest part of any field. We must all constantly work on our ability to communicate, which is actually not a single skill, but collection of important and interdependent skills such as listening, empathizing, speaking, logical organization of ideas, etc.

Arrogance: “Be off with you, lowly thumb scum!”

On the opposite end of the spectrum is just plain old arrogance. We think we already know what’s best; what could anyone else possibly have to add to the debate? One example is the “not invented here” mentality so prevalent in programming. Instead of using trusted and time-tested open-source libraries, companies will attempt to roll their own.

Of course it’s worth mentioning that oftentimes an outward display of arrogance is really masking deep-seated insecurity.

Fear and suspicion: “That thumb wants my job.”

Then there’s plain old fear for our position. If we feel even slightly incompetent we’re more likely to attempt to silence or distance ourselves from those we perceive as a threat to our position. If someone we view as a subordinate proffers a friendly opposable opinion, we could take it as a threat to our authority.

Learning to welcome opposable opinions

Feelings of insecurity run rampant among us, often causing us to tune out or bristle up in the face of an opposing opinion. We’re that poor index finger bracing for impact as it beholds a bulbous thumb looming menacingly on the horizon. But we need to get a grip. And to get a grip, a finger needs it’s thumb. Is there anything we can do to change our attitude?

Breathe

When someone has the guts to take a position opposite your own, the first thing you should do is nothing. Take a second to breathe calmly. Welcome the challenge with a friendly smile. Think.

Remember you need opposable opinions

Remind yourself that to get a “grip” on success, you need the diverse skill set of an entire team. A diverse skill set means different points of view. Embrace them.

Listening makes you stronger

Perhaps the “thumb” came at you in front of the entire team or company. You fear that giving ear to their idea might make you appear weaker or less capable. This is unlikely. The ability to truly listen is such a rare talent that many people are taken aback by it. By listening you might actually appear stronger.

Additionally, if the upstart really is trying to undermine your authority or cut you down in front of your peers, taking the time to listen calmly will allow you to override your initial urge to bristle up and say something foolish. Instead you’ll have the mental clarity to weigh your opponents arguments impassively. If their arguments contain solid points, admit as much. Kindly point out where they lack merit. Onlookers will appreciate your humility, humanity and control of the situation.

“Stupid” ideas probably aren’t

If an idea seems stupid at first glance, it probably isn’t. More likely, the idea’s originator fumbled the delivery or you misunderstood their intent. Ask for clarification. Remember that experts deal largely in intuition, which can be hard to verbalize. Allow them time to conceptualize. Depending on the circumstances, you might tactfully ask them to go work on it in private or with another team member and report back later.

When you can’t explain yourself

Perhaps you’re the expert and your intuition is clamoring for option X when the team is merrily bumbling toward option Y. Only trouble is, you can’t seem to convey your thought in intelligible speech. What can you do? Here are a few ideas you can try:

- Before you begin speaking, take a moment to form a mental outline of your arguments

- Try drawing a picture for everyone

- Attempt a real world illustration or comparison

- Admit that option Y doesn’t “feel right,” but you can’t explain why. Ask the team to convince you as to why option Y is the right way to go. Keep an open mind; maybe they’ll convince you to join them in option Y. Or perhaps hearing the arguments for option Y will help solidify your initially amorphous position against it, allowing you to better explain your preference of option X.

Sometimes you can’t explain yourself because you just aren’t comfortable with your stance on the matter. Be open to the idea that you might actually be wrong. Research your stance. Are you on a solid foundation, or have you built your argumentation on a collection of false premises? Your investigation may help you better explain yourself in the future, and could even reveal that the other side has more merit than you thought initially.

When your ideas are always the best

This is a problem. Your ideas aren’t always the best. It would be beneficial to take a long hard honest look at yourself and find out why you have this emotional need to be right about everything. Even visionaries as idolized as Steve Jobs didn’t always have the best ideas.

When you feel incompetent

First of all, remember that each of us knows but a drop in the great ocean of knowledge. We are incompetent, all of us, to varying degrees. Yet each of us has much to offer. If you are the novice, ask the dumb questions. Humbly ask others to explain things to you. You will learn, and the explainer will learn the subject better by having to teach it to another. Occasionally, you will end up uncovering the naked truth that the emperor is, in fact, not wearing any clothes. The organization as a whole will benefit.

The Peter principle tells us that we all tend to rise to our respective levels of incompetence in an organization. There is truth to that, but it doesn’t have to stop there if we continually self-educate. Never stop learning. Build up a list of acclaimed reading materials and stick to a solid program of reading and application.

Get a grip. Hold it. Dunk it.

The project looms large before you, and orange — strangely resembling a basketball. You reach out with a probing but confident hand, fingers outstretched, making decisive contact with the warm rubbery surface. You dribble once, twice, fake left. Fingers bear down hard on the spherical toy, thumb fully engaged opposite the little finger. One step, two steps, liftoff! — you’re airborne. A light breeze plays across the dense network of nerve endings in your face and fingers as you sail endlessly and inexorably through the night air toward the glittering red basket, the ball clutched firmly in your right hand as you bring it forward in a neat arc in front of you.

With a satisfying “swoosh” the ball plummets through the long nylon net. The spectators are on their feet in an instant. Slick with sweat, your fingers wrap briefly around the rim of the basket, standing stoically with bowed heads in honor of their stalwart companion and faithful harbinger of opposition – that old opposable thumb. Though bereft of words, the thumb nods back in understanding of their gesture. We couldn’t have done it without you.

In conclusion, don’t fear the “opposable opinions.” Respect and embrace them. Grasp them tightly as they counterbalance your own good ideas. You may not sink every shot, but where it matters most, you’ll win — together.